Monturiol’s Dream Excerpt

1. The Cap de Creus (Triangle Postals)

Prologue: The Vision

Lives do not have plots. For the most part, they accumulate events day by day like a stack of old newspapers. But sometimes someone glimpses a fixed point in the flux of things, a hard certainty around which the rest of life turns like the pages of a good novel. Narcís Monturiol i Estarriol believed he had discovered the point of his life on the rocky shores of the Cap the Creus when he saved the life of a coral diver and conceived of a craft capable of taking humankind safely under the sea. Everything he had been and everything he hoped to be made sense to him in light of this fantastic vision. The submarine “is the soul of my life,” he declared. “Without it my earthly existence would have no purpose.”

The Cap de Creus – the ‘Cape of the Crosses’ – lies at the end of a ragged peninsula on the northernmost coast of Spanish Catalonia. The rocky bed of the cape has withstood the erosion that has eaten into the softer coastline surrounding it. A wind called the tramuntana blows down constantly from the nearby Pyrenees Mountains and sweeps across the peninsula to the sea. Local lore has it that the wind can drive people insane – which explains the high incidence of eccentricity and deviant behavior in the area, or so they say. Where the land meets the water, the wind and the waves have performed a certain kind of magic, carving surreal curves and ghostly shapes in the stone.

2. The rocky shores of the Cap de Creus (own photo)

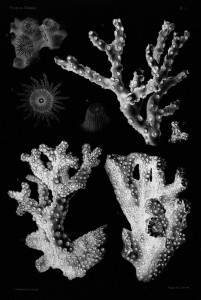

Just off the shore, at depths of 10 to 40 meters, coral covers the submerged bed of rocks like a prickly blanket of crushed glass, coloring the sea bottom in patches of crimson, rusty red, rose, tangerine, caramel, and bone-white. The coral is the work of millions of tiny animals, whose mineral-rich secretions accumulate over years to form these motley, plant-like stones. In the age before plastics, humans placed extraordinary value on coral. Smaller chips were prized for earrings, necklaces, bracelets, and other jewelry. The rare, larger pieces of 1 to 3 centimeters in diameter were used to make elaborate candelabras, and commanded exorbitant prices. Crimson was the favored hue, especially in the markets of South Asia, where much of the coral was sold. The coral of the Cap de Creus was long considered the finest in Spain, and possibly the best in the Mediterranean.

3. Coral in the nineteenth century

“Report on the Florida Reefs”, 1880, based on field studies by the renowned biologist Louis Agassiz. (Negative; National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, Department of Commerce)

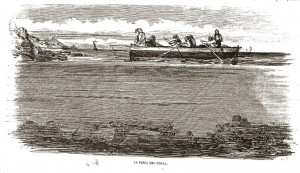

At the peak of the coral age, coral diving was the chief source of employment in the fishing village of Cadaqués, an afternoon’s walk down the coast from the Cap de Creus. Typically, the divers worked in teams. They would suspend a basket from a boat, and then each would take his turn to plunge as much as 20 meters under water. In the few minutes that he could hold his breath, the diver would chip off bits of razor-sharp coral and drop them into the basket. It was a hazardous way to make a living. The risk of drowning or injury on the rocks and coral was substantial. The occasional shark attack only made matters worse. “Often the diver does not return, or else comes to the surface mutilated or dying,” said a reporter of the time, “his blood giving to the waves the color of precisely the product he coveted.”

4. Coral diving, 1859

(Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona)

One day on the shores of the Cap de Creus, Narcís Monturiol came upon a group of divers huddled around the inert body of one of their fellows. The fishermen flailed their stricken colleague frantically, trying to beat the seawater out of his lungs, but to no avail. Narcís being Narcís, he couldn’t just stand there. He rushed in among the crowd to help. He grabbed the man by the feet, lifted him up so that his head pointed down, and allowed the force of gravity to pull the water out. The diver spluttered back to consciousness, still clutching the red gold it had nearly cost him his life to acquire.

It was around this time that Monturiol first conceived of the possibility of a craft capable of navigating underwater. Later, as he walked the same stretch of the cape in the company of a close friend, he revealed his secret ambition to build such a vessel. He called it a ‘fish-boat’ – an ‘Ictí-neo’, he said, using the ancient Greek terms for ‘fish’ and ‘boat’. We would have called it a submarine.